Time Travel

When built it was considered among the boldest works of engineering ever made, while now it makes us smile knowing that they thought as much. However, we are talking about the mid-19th century when most modern engineering had still to come. Moreover, those times were still the early days of the railways when there were only short stretches of rails that mesmerized people simply because, until then, no one had ever seen a train puffing through the countryside. In short, it happened that two brothers, from a remote village of the Apennine mountains, decided to propose to the Grand Duke of Tuscany (an enlightened ruler, willing to invest), the construction of a railway line that would allow transporting goods and people across the mountains much faster than by using the existing roads. However, it was easier said than done, as Protche, the French engineer in charge of project design, would soon realize. He was appointed with the consent of the Viennese government who was happy to have at its disposal, if needed, a quick means of transportation for troops and guns to dispatch to Southern Italy when deemed necessary. That “good man” Protche, who did not lack in boldness, had essentially three problems to solve:

1) Limit to a minimum the length of tunnels. The further down they would dug, the longer they would become.

2) Ensure that slopes would permit trains to stop at all stations along the line without descending at too high of a speed.

3) Provide tunnels with a ventilation system that would allow enough oxygen penetration, thus permitting the combustion of coal needed by the train boilers and, even more importantly, avoiding the real possibility that tunnels would became gas chamber, ensuring the survival of passengers.

This latter problem was closely connected to the first since the lower the tunnels, the longer the ventilation shafts would be, making their proper ventilation more difficult.

The second problem, small in appearance, was rather difficult to solve. The longitudinal section of the Apennine Mountains is a sort of rectangle resting on its hypotenuse, with the Tuscan side representing the shorter, steeper side. In this context, how would it be possible to bring a train at its highest altitude while minimizing the length of tunnels, the slope of the tracks and the depth of the ventilation shafts?

Fig. 1 - longitudinal section of Appennines

The solution was the introduction of two consecutive loop bends, some tunnelled, which reduced the tracks’ slope, but lengthening the journey as a result. This solution created a paradoxical situation noticeable even today. In some parts of the railway it appears that the passing train goes towards Pistoia while, on the contrary, it is going on the opposite route, towards Porretta Terme and the Emilia region.

Fig. 2 - outline of the loop bends

In some stretches of the railroad, despite all efforts, slopes remained excessive with the possibility that, without appropriate measures, trains directed downwards would end up with overheated brakes. In addition, tracks made slippery by oil spilling from the trains, would have made it impossible to stop on time, especially at some intermediate stations on the route of the Tuscan plains. To solve this problem Protche added deceleration lanes, resembling jumping trampolines used for skiing. This way trains speeding downhill had time to slowly loose speed and slow down easily to their stations. To facilitate trains going in the opposite direction, some of the stations were instead provided with acceleration ramps, allowing trains to pick up enough speed to climb the mountains.

Fig. 3 - Building a deceleration ramp

The third problem was the most difficult to solve and, in fact, it was never completely addressed until the electrification of the railway lines. To supply the required energy for handling the impervious ascent, even at low speed, boilers had to be fed with large amounts of coal emitting considerable smoke. Tunnels were provided with aeration shafts – in some cases more than one hundred meters deep – and large fans – designed and installed by the Saccardo firm. However, train engineers would often emerge unconscious from a tunnel because of the excessive combustion fumes, thus leaving trains to fend for themselves.

Fig. 4 - Ventilation shaft at a train's passing

Fig. 5 - Extract of the register of accidents

This happened especially on exiting the San Mommè Gallery, the longest at almost 3 km (2 miles), requiring to post a team of supply drivers at tunnel exits, ready to jump on trains to take the place of unconscious colleagues when needed. Passengers did not fare much better.

Records show that at the pick of its activity, in the railway transited up to 90 convoys per day, made of 12-13 wagons each, requiring, at the Pracchia mountain pass, three locomotives, two at the head and one at the tail. At that station, now desolately empty, there were 20 tracks and 35 exchanges, hydraulically operated with a forced water system. At this station transited every day tens of thousands of passengers, something hard to believe today by looking at the surrounding empty countryside. To cover the entire distance – about 100 km from Pistoia to Bologna – it required almost five hours, a real odyssey.

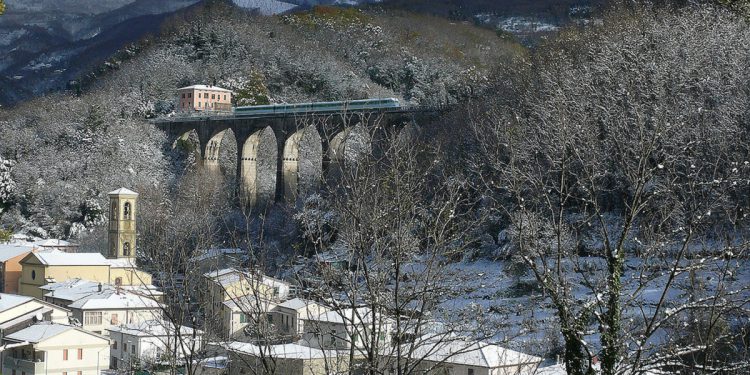

The construction of the railway, which took almost ten years to complete, needed one hundred thousand people, mostly migrants from other parts of Italy who built entire towns in proximity to rail stations and who decided to remain after the rail line inauguration. A total of 47 tunnels and 30 viaducts were required. A colossal enterprise that after a few decades, with the opening of the direct track line connecting Florence, Prato and Bologna, became redundant and useless.

Fig. 6 - Piteccio's viaduct

What is left of the glorious days of this railway are only the smallest stations located in secluded wooded areas. Local conservation groups are now trying to preserve them antagonizing the government railway agency that, pushed by public outrage, wearily and reluctantly, is obliged to repair the numerous landslides that make maintenance of this line difficult and expensive. Repairs will continue only until there will be someone strongly wishing this rail line to continue existing. With the electrification and the elimination of freight transport – nowadays available in far easier routes – travel times are been shortened by about half. However, the whole Pistoia-Bologna trip – now no longer made available – would require well over two hours to complete, longer than it would take to a good cyclist.

Fig. 7 - Castagno's station

Most of the numerous villages perched on the mountain slopes, built because of the railway, are now depopulated. Until the mid-70s, some of them had no other means of access than the train line. Train wagons that at one time came down the hills full of schoolchildren, are now almost empty. The few remaining users include tourists, fascinated not just by the landscape, but also by the discovery that such a short trip can take such a long time.

We thank all of Modus’ numerous readers, who, with their continuous attention make sense of our work.

For those who would like to be informed in real-time of our online publications, and have an active profile on Facebook, we recommend giving likes on the Modus fan page: they will be able to directly link to all newly published articles.

The editorial staff

1 lettore ha messo "mi piace"