Hannibal’s journey

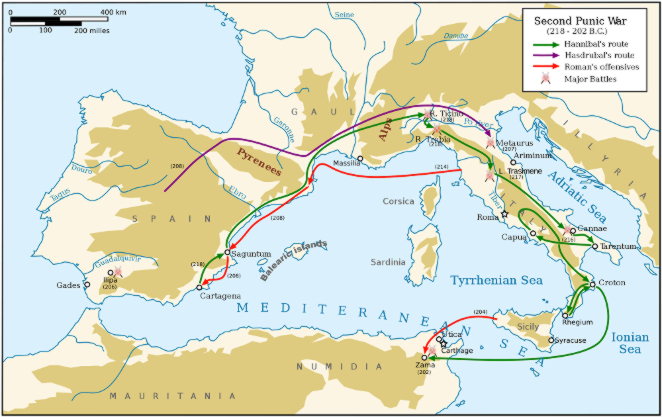

In the fall of 218 b.c. a Carthaginian army, that had left Spain six months before, arrived in the Po valley through one of the passes, never clearly identified, which are between the Little Mont Cenis and the Viso.

It was an exhausted army decimated by the cold, disease and the continuing and unnecessary battles fought along the way against the inhabitants of the territories that it had crossed; 20,000 to 25,000 men, about half of those who had left, including infantry and cavalry, had survived the crazy and unthinkable feat of crossing the Alps and if there hadn’t been Roman legions waiting, the Second Punic War would never have begun, while world history would have to do without one of its biggest stars.

The Col du Petit Mont Cenis, by Laura Monteleone

Hannibal was then 29 years old, and from the day he had become chief of the Carthaginian army of Spain, three years before, he had worked to build a casus belli that would allow him to make war on Rome, finding it quickly in the conquest of Sagunto, which had fostered the albeit late Roman reaction.

Publio Cornelius Scipio, the father of the future African, Consul that year, had left for Spain with the intention to close the challenge there, but had failed to intercept the Carthaginian army, because Hannibal, who did not intend to fight anywhere but in Italy, had refused to engage; whatever ideas Scipio had about Hannibal’s plans, that he would ever cross the Alps was not considered, and even if he had ever made it to Italy, what could he have done with 50,000 men when Rome could field more than half a million?

Map of the Second Punic War(Click the image to enlarge)

Hannibal for his part was not afraid of half a million Romans in arms; he was a man that combined the Punic soul to Hellenistic training, he had a Spartan as a teacher, and had spent his entire life preparing to become what would he soon proved to be, the greatest general of antiquity: the Barcids (from barak, lightning in Phoenician language) were one of the oldest and most powerful families of Carthage, to the point that in two generations of Hamilcar and Hannibal the family at times overlapped the state, or parts thereof.

Hannibal knew for sure, he had learned it from Alexander, that no army with more than 50,000 men could retain the ability to maneuver, and static armies are always defeated; he knew, always from Alexander, that the use of combined arms, infantry and cavalry, was able to overwhelm armies, like the Romans, that fought only or mainly on foot; he was also at the head of an army of professionals, his soldiers were technically his employees, and would remain always faithful until the death, while the Roman armies were conscripted armies, made up barely trained farmers, and led by generals with fixed tours of duty, which would expire at the end of the Consular year.

Finally the Romans fought in the manner of Hector and Achilles, in the open, with the deployed armies and with full confidence in the chivalry of the enemy, because the relationship between “righteous enemies” are governed by the “fides“, while he, Hannibal, fought like Ulysses, because “modern” war is based on “metis“, a concept that the Romans then could not even remotely understand.

No, as absurd as it might seem, Hannibal was not afraid of being defeated in any pitched battle, and was counting on being able, in the wake of the military successes, to separate from allegiance to Rome a sufficient number of allies to weaken the Republic and keep her from harming or suppressing Carthage; the Hannibal’s plan, let’s state it outright, will be a military success and a political disaster.

The Trebia today in Rivergaro, in the foothills in which Scipio sought refuge from Hannibal's army.

As of the winter of 218, no Roman army was headquartered at the foot of the western Alps, and Hannibal, coming down from the pass, that remains unknown to this day, must have smiled, despite losses and fatigue, thinking that he had avoided the only event that he had been really afraid of: that of being forced to fight without having choosen time and place.

The next two years have become a trite jingle in modern history books: the Ticino, the Trebia, the Trasimene and finally Cannae have all become textbook battles, in which Hannibal rewrote the art of war for centuries to come; what gave them depth were not so much the victories in themselves, as much as the variety of tactical solutions applied and the favorable ratio of losses to would merit complete fascination.

The battle of Ticino was actually a simple clash of cavalries, little more than a skirmish, destined to be famous mostly because Scipio was injured, and especially because his young son began his long apprenticeship as a soldier by saving his father’s life.

Bust of Publio Cornelius Scipio Africanus

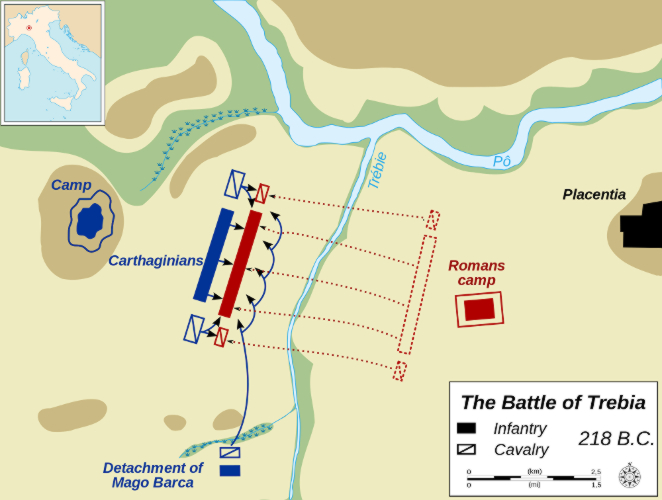

The battle of the Trebia (River) was the first real taste of the Hannibalic war: the Romans were attacked before dawn on December 25th, while they were intent in the morning ablutions, by a refreshed army, that had been warmed by fires and was well placed behing cover, gradually lured out on the field, divided into two parts on opposite banks of the river, they were soon soaking wet and cold as well as hungry, and attacked from time to time from contingents that were refreshed and dry, taking turns at the Romans; before dusk around half the army that managed to escape left on the ground between 15,000 and 20,000 dead legionaries, and even if we do not know the Carthaginian losses, they will hardly have been higher than those of other battles (more or less 10 % of those suffered by the Romans).

The Battle of Lake Trasimene (Click the image to enlarge)

The Battle of Lake Trasimene was an ambush, on a foggy morning, against the Roman army marching on the shore of the lake, at a point where it was impossible for them to move in any direction that wouldn’t have them end up in the water, where in effect many drowned legionnaires drowned: 15,000 dead and 15,000 prisoners, compared with only 1,500 Carthaginians fallen (in fact the majority of the losses are always recorded among the Gauls, for their wild way of fighting, unruly and unmanageable, always ended up in the very points where the Punic lines, as per Hannibal’s plan, had yielded).

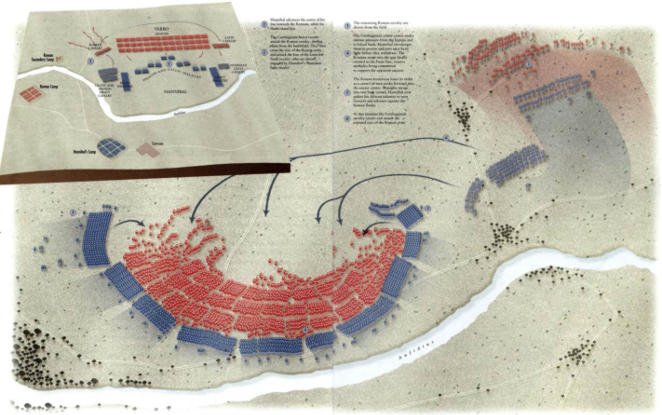

The battle of Cannae, 80,000 Romans versus 40,000 Carthaginians, was the largest maneuver of encirclement of military history: Hannibal’s formation, a convex line facing the enemy, with the center at first doing the fighting and with the wings deployed farther back and weapons ready, began to yield and retreat at the contact point, becoming progressively concave, while the Punic right and left cavalries, superior in number and training, overran the Roman ones; when the line had been sufficiently concave, the Carthaginian wings closed and converged on the Romans, while the cavalry attacking from behind, had sprung a perfect trap.

[slideshow_deploy id=’17433′]

The battle of Cannae, progression of the formations in 5 slides

It is said that the “tuna trap” was invented by the Phoenicians, and perhaps this battle is illustrative: 50,000 Romans were massacred in one afternoon, all with stabbing weapons in a space no bigger than a football field, and while again the young Scipio was saving skin musing on the art of war, there remained on the ground a hundred senators and a few dozen former consuls and magistrates, reflecting how differently the ancient world viewed the concept of leadership.

Topography and deployments on the field at the beginning of the Battle of Cannae.

(Click image to enlarge)

With the 6,000 men fell at Cannae, Hannibal had lost no more than 10,000 in barely two years of fighting, less than those who perished in the journey from Spain, while Rome had losses that exceeded 100,000 units, including many prisoners, and above all, as a legacy of these massacres, felt a pervasive sense of helplessness in the face of the enemy: the Romans had been defeated across the board, surclassed strategically without appeal, but they denied the evidence and when Hannibal offered negotiations they simply refused to consider the idea.

What followed was the first “world war” in history, exhausting, bloody, with th control of cities changing from hand to hand, with looted countrysides and a progressive impoverishment of the entire Italian peninsula, a war in which Hannibal brought forth more victories without conceding any real defeats, but he would indeed lose eventually, because the Republic already had a “national” structure, it wasn’t a simple city-state anymore, and especially because, while resisting against all logic, it managed to change its military organization and the rules for granting command; when in 203 Hannibal was recalled to Carthage, the young Scipio had already taken Spain from the Carthaginians and, having traversed into Africa, in just two years of war had devastated the Punic city, showing that he had learned and perfected the art of war and had made the most of the teachings of what he must have considered his real teacher.

The Battle of Zama

At Zama, Scipio, who was after all a great general, won, but his victory, achieved because of clear conditions of superiority (a professional army against an army that for two thirds was mamade of poorly trained recruits) was perhaps tied more to luck than historiography has not later recognized.

At the Campi Magni Scipio had defeated a Punic army by surrounding it without using his cavalry. He had placed the hastati in the first-row, forming the battle line, and placed behind them the centuriae of principes and triarii . The two divisions were of the same width, and this allowed Scipio to slide the principes and triarii alongside the two armies, to turn behind the Carthaginian rear to close it in a vice, perfecting Hannibal’s own maneuver. At Zama he tried to repeat the same pattern, but things went differently. The Carthaginian cavalry, now irrelevant to the Roman one thanks to the change of allegiance of the Numidians, had escaped only to be pursued, and just as Scipio was about to give the order of encirclement, he realized that the third row of Carthaginian veterans of the Italian campaigns had remained behind, leaving space between itself and the first line prevented the execution of the encircling maneuver that had been carried out at the Campi Magni: the pupil had not yet surpassed the master.

Battle of Campi Magni - pincer maneuver around Celtiberi.

Scipio was forced to give up and to expand or lighten his line-up to pair up to the Carthaginians, so as not to risk his being surrounded, and the battle became a fight to the death between the veterans of the Italian campaigns, who were the fresher troops, and the legions of the survivors of Cannae, who had been in punishment since 216; at the end the battle and with it the war was won by the Romans, perhaps undeservedly, thanks to the return of the Numidian cavalry.

Hannibal was then 46, and a whole life ahead of him; besides being a great leader, ruthless in war, but not personally cruel, he was an educated man, a polyglot, art-loving, of sober customs, excellent agronomist, astute businessman and a subtle politician.

He negotiated peace with the Romans, took his men as farmers to cultivate his lands, the wealth of his family was immense, and became sufet (head of the government of Carthage), with the probable intention of turning it into a personal lordship: when he forced the Punic aristocracy to pay taxes, the nobility turned against him and, asking assistance from the Romans, forced him into exile.

Artassa, in present-day Armenia

He was still a soldier, in the service of Antiochus of Ephesus, but without any real military power, then he was an urban planner, first in Artassa, Armenia, where he built the new capital of the kingdom, Artaxana, and then to Bithynia, where he built in honor of King Prusia present-day Bursa.

Prusia I, King of Bitinia,in present-day Anatolia

Eventually the Romans, weary of his attempts to push the Hellenic world to join forces against Rome, asked King Prusia for his head, the ruler agreed, and for that matter, how could he refuse …; we all know how it ended, we studied it in school, Hannibal preferred death, and concluded his journey 67 years old on the shores of the Black Sea; what remains in history of Hannibal’s journey?

The Hannibal Castle in Libissa where he died, near present Gebze, 40 km east of Byzantium.

In my opinion a dream, that of a man who had imagined to be Alexander and to continue his accomplishments, but as the world yielded before the armed Macedonians, and became Hellenistic almost with enthusiasm, in front of those armies of Hannibal’s the world retracted, and resisted, and fought to the death. Perhaps the difference lies in the fact that Alexander represented a world and a culture, Hellenism, in the moment of its greatest expansion, while Hannibal represented himself, someone who wanted to impose on the world the same culture but now heading towards its decadence; the Second Punic War was actually the Hannibalic War, the war of a man against a state, and probably that’s why it was impossible to win, in spite of all the battles he dominated, including Zama, where the gods had probably turned the other way.

Personally I think it was a shame, because I think that Greek culture would have opposed a far more solid bulwark to the Judeo-Christian culture and the disasters that it ended up causing in world history, but this is impossible to prove.

![]()

We thank all the many readers of Modus, that with their regular or sporadic visits give meaning to our work.

To those who would like to be informed in real-time about our publications, and have an active profile on Facebook, we recommend to add your “like” to the fan page : you will receive links to all our new articles.

The editors