Black Lives Matter, Italian Style

Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter

Montanelli’s statue and the removal of consciousness about Italy’s colonial past.

The recent Black Lives Matter movement protests againts police brutality in the USA, have inspired similar protests all over the world. As part of the recent demonstrations in Italy against racism, the statue of the celebrated Italian journalist Montanelli was stained with red paint. Indro Montanelli (1909-2001) is a celebrated Italian journalist whose biography, like several American historical personalities whose statues have been recently dismantled is tainted with the scourge of racism and slavery. Contrary to what is happening in the USA, most opinion makers in Italy have decisively sided against the protesters, marginalizing them and describing the statue’s desecration as an act against humanity.

In Italy, the Black Lives Matter movement, contrary to other American socio-cultural aspects, will probably remain linked only to the thematics of that nation, since too many in Italy, including journalists of prestigious newspapers, consider it to be something only to do with the descendants of overseas slaves and their masters. Whilst we are all aware of the persistent racism in the USA, too often we pretend to forget our own recent past, tainted by racism and slavery. On the other hand, who wants to remember or be told that while slavery in the USA was abolished in 1865, in our colonies it was de facto outlawed only in 1938?

It was an abject slavery, unopenly declared and tacitly promoted by the Fascist government of that time. It was protected by the high military commanders who themselves practiced this form of slavery on the skin of black minors, thereby denying them both their freedom and their adolescence. A reality still today diminished by our establishment that has decided that our historical past is not what it is, but rather what they would like it to be. To paraphrase Montanelli if we are scandalized by what happened, it is our own fault. (Corriere della Sera, February 12, 2000).

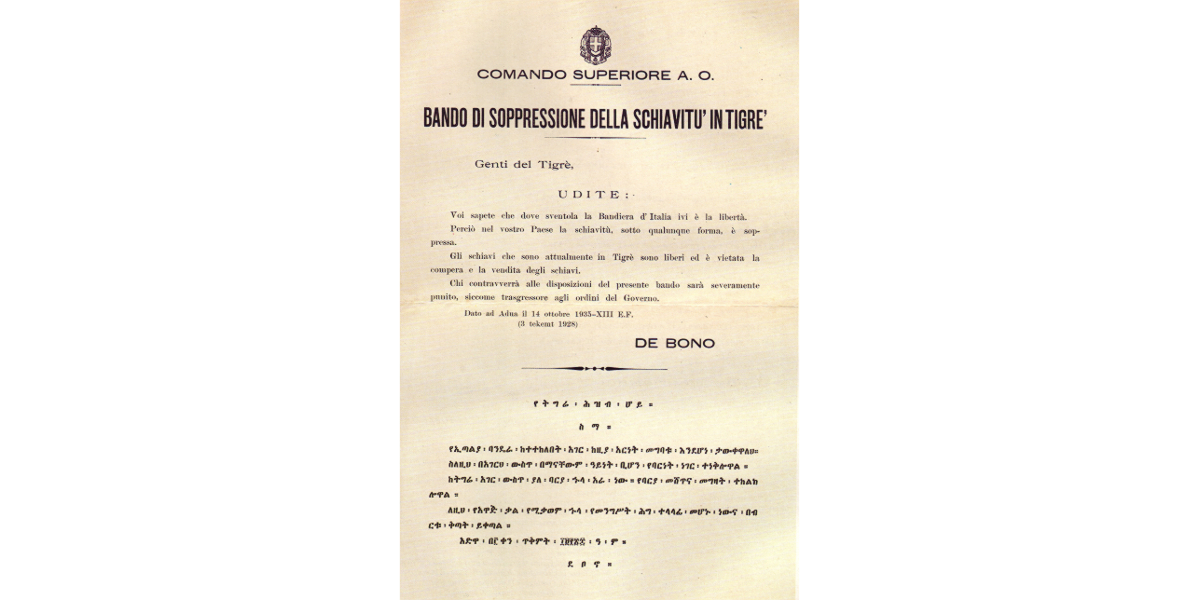

Edict banning slavery in Tigrè, 1935 - Click image for higher resolution

Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter

«The staining of Montanelli’s statue for racism and rape is a gesture anyone should condemn» This writes the prestigious Italian newspaper La Repubblica on June 16, 2020. Pathetic and senseless the scarring of the statue of Montanelli, titles an article of 4 May 2018 in the online Milano Post, which echoes a theme already proposed on July 20, 2015 by the Montanelli-Bassi Foundation in a blog titled: An unjust and instrumental accusation. On June 14, 2020 Corriere della Sera, the most circulated Italian newspaper, in the article Outrage to Montanelli: pretentious purpose, shameful method, goes much further. The smearing of the statue is portrayed as «stupid emulation» and a sin against «humanity, a virtue that Montanelli had, while his smearers lack».

Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter

These are strong words, full of indignation and disapproval against those who have dared to protest against the silencing of our uncomfortable past. Yet the systematic racism perpetrated in our former colonies, the Madamato(1) – a euphemism to describe the much despicable slavery and serial rape perpetrated on defenceless minors – is a historical truth.

If we really believe in the message of Black Lives Matter coming from overseas, it would be most appropriate to include the lives of those black teenagers that our nation has enslaved and cheerfully tormented in our former African colonies. At the beginning of the African hostilities in Ethiopia(2), signalled by the conquest of the Tigray region in 1935, Italy officially banned the local practice of slavery, a propaganda operation in support of the regime’s colonialism, masking the aggression as bearer of civilization. The ban, as it happened, concerned only the locals, becoming a cover for the conquerors to treat the locals at their convenience.

We cannot and must not reduce our colonial past to petty individual indiscretions and treat with disdain those who, like the young statue smearers, call that part of our past by its real name: racism, slavery, mass rape and pedophilia. Today we must indeed give credit to the Montanelli. Both for his direct contribution in having freely given us a true, sincere, direct and authoritative distant testimony of our colonial policy of racial discrimination, and for his indirect contribution through its statue desacration. This event having raised awarness to the persistence of racism in our collective consciousness, lasting far beyond the end of fascism. As for our humanity in colonial times, it is sufficient to review the freely expressed testimony of Montanelli, whose memory so many of our opinion makers are scrambling to defend.

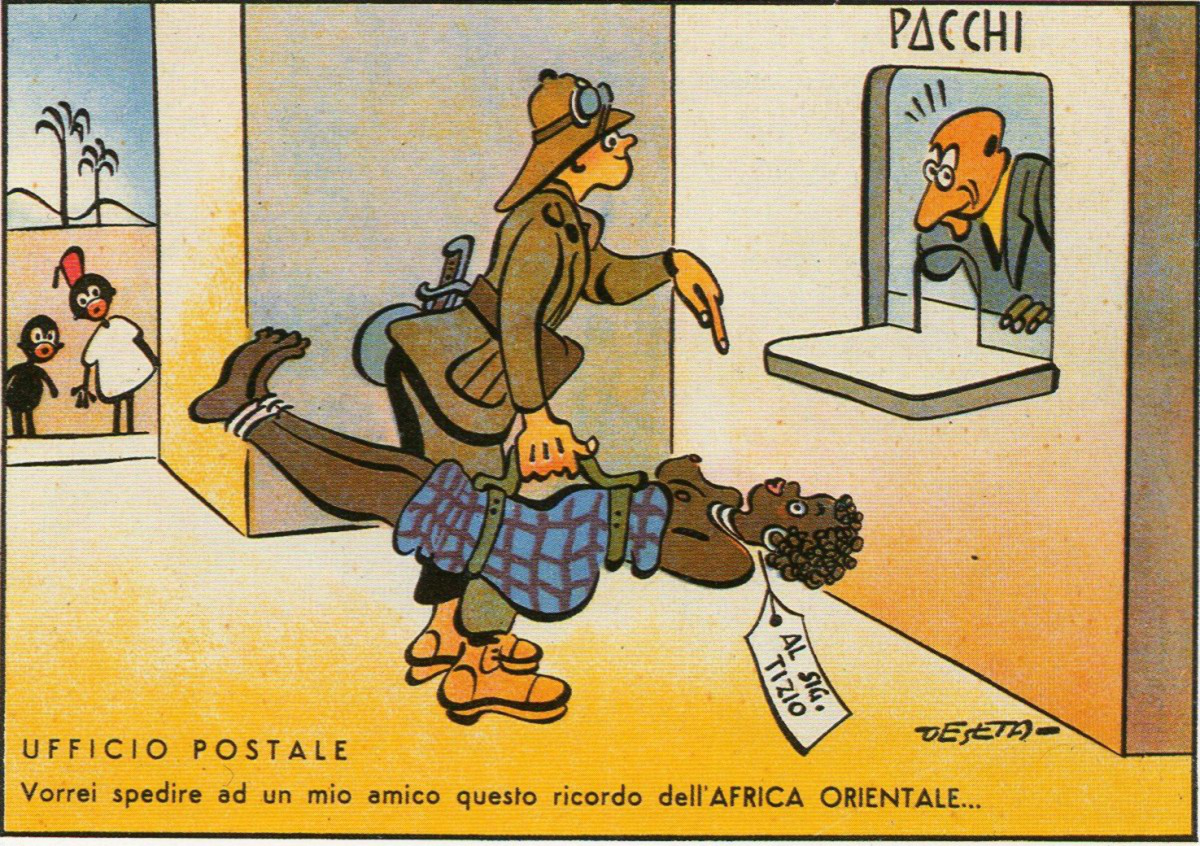

Enrico De Seta, satirical cartoon on the war in Ethiopia

Contrary to today’s business practises, the contract with which the journalist had – to use Montanelli’s own term – ‘leased’ a twelve-year-old child, had no deadlines and no penalties, nor provisions regarding the conditions of return. It was therefore all at the convenience of the customer, who could get rid of the purchase when and how he pleased, without any obligations whatsoever. This leasing, as Montanelli keeps informing us, also had a performance guarantee. This was evidenced by the fact that, since the child was too young to understand what her duties were, she was persuaded with ways that Montanelli had the humanity not to disclose in detail.

The cost of the lease, which was agreed upon after two days of negotiations, was a real bargain: «I bought her in Saganeiti, Etiopia, together with a horse and a rifle, all for 500 lire». At that time in Italy the monthly wages of factory workers and rural laborers ranged between 150 and 300 lire, while that of a mid-level office worker ranged from 400 to 600 lire. The monthly wage of an army general was about 3000 lire. The average monthly cost of a rental dwellings in Italy ranged from 200 to 300 lire. Nowadays, even a prized breed puppy dog would certainly cost more. However, as far as the journalist was concerned, what he bought was anything but a prized breed. In fact, according to him: «She was a docile little animal. I put her in a tucul (3) with some chickens … I struggled considerably in overcoming her smell, due to the goat tallow she used on her hair, and even more so to begin a sexual relationship with her… it took the brutal intervention of her mother to convince her ».

The bad smell of goat was added to that of the hens and Montanelli had to deal with it, since purchasing another tucul would be an additional expense. In the tucul, as it is easy to imagine, Montanelli certainly could not have classy parties. However, from the expression on the journalist’s face while recounting his heroic-erotic deeds, it can be deduced that they surely were happy feasts complete with home-rased chickens. Those were restrictive times for Italy, with sanctions being placed on it by the world’s democracies on a mistreated country. All because it was claiming its place in the sun while its soldiers were having a little fun on the side with local girls, when not throwing arial bombs and suffocating gas on the Ethiopians.

Regarding the age of the girl, as Montanelli tells us, «She was 12 years old, but don’t take me for a brute: at 12 years of age those ones are already women … I needed a woman at that age. My non-commissioned officer bought it for me … ». The brute would therefore be his African non-commissioned officer. However, it would be unfair to attribute him unjust faults, since he certainly could not find a beautiful eighteen-year-old black girl at a slave market. British and Dutch slaves ships who supplied a thriving slave market alas were long gone, as the American Secession war had gone badly.

Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter

At this point is necessary to seriously question whether this brand new form of slavery Italian style, with its leasing format, was widely practiced by the many Italians present in those years in the occupied African lands. The conditions of the military conscripts were bad, with them being poorly paid and subjected to all kinds of harassment by their officers. In addition to the military, there were many Italian workers in Ethiopia, whose salary was 25 – 30 lire per day for ten hours of work on weekdays and five hours on holidays. Those instead who had too much money and time for entertainment, way too much actually, were the high officers and the volunteers of fascist militia, which included Montanelli. Almost all of them enlisting with an ardent patriotic spirit and who were thrilled at the thought of bringing their model of civilization to the black femail population.

However, finding volunteers to get killed for the cause of the Italian civilization was not an easy task, thereby requiring Mussolini’s genius to solve it. The aggression in Africa was therefore cloaked in the glorious dreams of a Roman Empire at last reborn after twenty centuries. Given that that was not convincing enough, it was aided by the spreading of all kind of not so suttle allusions to available African women, were presented in popular songs, such as the popular Faccetta Nera (4), as well as in postcards, newspapers and magazines. They were illustrated as busty and eager girls, well packaged and ready to be consumed as it is done today with popular disposable products(5).

All of this resulted in a subtle operation with the silent endorsement of racism, slavery, abuse and sexual exploitation on a mass scale, in which pedophilia thrived. Thus, while the fascist censorship silenced the dissidents by singling them out as enemies of the homeland, it promoted the virtual legalization of a visceral racism, which lead to murder and violence of all kinds in the name of an undisputed and undeniable racial superiority. In January 1936, onthe eve of our armed aggression in Ethiopia, the young journalist Montanelli wrote in the party magazine Civiltà Fascista (Fascist Civilization): «We will never be dominators if we do not acquire the exact awareness of our fatal superiority. Fraternize with niggers is impossible. We cannot; we must not. At least not until we will give them a civilization».

1923, the Italian Governor, and Quadrumviro of the March on Rome, Cesare Maria De Vecchi lands in Mogadishu (bald to the left of the center).

Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter

The enslavement of African girls and children was done openly. The mission of bringing them a civilization resulted solely in unwanted offspring who were, needless to say, abandoned to their destiny. As for Montanelli’s humanity, he himself informs us that when his mission was over and he had to get rid of the child, instead of bringing her back to her parents and losing the investment, he tranfered his lease – net of amortization – to General Alessandro Pirzio Biroli. This person was none other than the governor of the Amara Duration area, an office he held from June 1, 1936 to December 15, 1937. This gentleman, at the time in his sixties, having a montly salary that we know was of 3,000 lire, was able to put up on a harem full of minors. The envy of even the one set up by Berlusconi, one of Italy’s greatest post WW2 politicians and, incidentally a person even older than the general.

The military history of Montanelli’s business partner would soon become even more edifying. From October 3, 1941 to July 20, 1943 he became Governor of Montenegro, sent there to suppress a revolt of the local populations. He took German methods as an example, improving them by ordering reprisals on a far larger scale: 50 unarmed hostages were put to death for each Italian soldier killed or officers wounded. Later on in 1943, with Italy’s armistice, he renegad on his oath to the fatherland and to his king by joining the newly formed Fascist Republic of Mussolini in chasing Italian partisans. As it happened, Montanelli at the time was hiding in Switzerland, thus avoiding any possibility of having these two business partners slaughtering each other. After the war, as it happened, in addition to Mussolini, the new democratic Italian republic also recognized the merits of the general. In fact, while many German high officers, either ended up in jail or hiding in South America, General Biroli freely revelled in his war memories with a lavish pension (6). This despite the fact that Yugoslavia clamored for its extradition, which was never granted, since our country, the cradle of humanity, would have never negotiated with a communist country, dominated by evil

It seems that Montanelli had regard not only for General Biroli but for all the commanders of the Italian-German alliance. This can be seen in the journalist’s defense of the German commander Herbert Kappler. He was virtually a lone defender of Kappler in Italy, yet his defence was made without any sort of hesitation. Incidentally, Kappler was tried and convicted in Italy for the so called Massacre of the Fosse Ardeatine, the murder of unarmed Italian civilians in reprisal for the killing in Rome of German soldiers by Italian partizans. Unlike General Biroli, the ratio of Germans casualties to Italian hostages killed by this Nazi criminal was little more than one to ten.

The tone of the fascist propaganda in arousing enthusiasm for the African enterprise, although successful in recruiting young volunteers, did not produce the desired results. This was because, rather than a war of conquest, the Ethiopian colonial enterprise was perceived by the majority of Italian volunteers as an erotic vacation abroad, not dissimilar to those later taken by Italian males in the years of Italy’s economic boom. Thus Montanelli described his warlike undertakings in his memoirs on the war in Ethiopia: «This war is for us like a beautiful long holiday, given to us by the Great Santa [Mussolini] as a reward for thirteen years of school. And, said between us, it was about time»(7). These feelings were echoed by Vittorio Mussolini, eldest son of the Duce and leading exponent of a new Italic lineage, the legitimate heirs to the glories of Ancient Rome: «War is a sport, the most beautiful, the most fulfilling … An education to become real men»(8).

To understand how and why Italy lost the war, there is certainly no need to read Storia d’Italia, cowritten by the famous journalist. In this popular history publication, incidentally, there is no mention of the racial matrix of our colonialism, of the Madamato or of Santa’s present to the Fascist Colonial volunteers. However, how could we not agree with these militia volunteers, considering that for the vast majority of them it was indeed a great holiday and a conflict virtually causing them no harm? The War in Ethiopia in fact counted many Italian casualties, the vast majority of whom turned out to be draft soldiers, poor devils who certainly could not afford vacations, let alone overseas and in a place where there was a war.

In a historical twist of irony, the endorsement by the fascist regime of the systematic slavery (9) the Madamato virtually ended when racism in Italy went from being tacitly supported by the fascist apparatus to being implicitly prohibited by the Fascist racial laws enacted in 1938 (10). As often happened and still happens in our country, the legislative text did not mentioned slavery. Its prohibition was simply the result of the official outlaw of all sexual relations between nationals and inferior races. A ridiculous measure that was adopted in the hope of preventing that our lineage would loose its purity, in spite of two thousand years of history of colonization and invasions by Greek, Saracens, Viking, Moors, Lombards, Turks, Germans, Slavs, etc. Racism and colonialism are two aspects of the same problem. While racism may be a phenomenon in itself, colonialism is closely related to racism. In our country, in fact, colonial prevarication was presented as bearer of civilization, within a discourse deeply imbued by the concept of racial superiority. It is an operation that can only be successful at large scale by an ideological cover,relying on the removal of conscious reasoning, aiming instead at the dark parts of the unconscious.

Racism, as a collective pseudo-scientific ideology, has roots dating back in Italy to our national unification in the 1860s (11). It was carried out by the entire political and intellectual establishment of the time, including its most progressive sector. Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, a lawyer and prominent politician of the Italian Historical Left, theorizes racism as part of the modern doctrine of the law of nations. Mancini in his writings and speeches defines race, «expression of identity of origin and blood», and national identity as «the most tenacious bond between individuals of the same lineage in comparison with those who are foreign to it». Mancini, thus, inaugurates the colonial political ideology of our young nation, perceived as a civilization mission and as a crusade of civilization against barbarism. Another important exponent of the Italian cultural progressivism of those years is Giovanni Bovio. According to the philosopher and jurist, the best breeds have the duty to transform the worst breeds, if necessary even with violence. This in accordance with the principle of the natural law of selection, valid both for an individual and for a whole population. For the scholar, therefore, race superiority and inferiority has a scientific basis that justifies an operation of civilization. Ironically, one of the examples of barbarism in the third world cited by the scholar is Ethiopia where, according to him, anthropophagy and moral debauchery were prominent. The later deeds of Montanelli and his colonial comrades will prove him right.

In this political and cultural context, Italian Fascism grew and prospered. Considering all the evils it brought, Fascism had at least the merit of providing justification and a cover to Italian racism raised to a system, assumung in the current Italian discourse both its own and preceding faults. The sufferings of a war, which we entered into simply out of stupidity, was instrumental in spreading a pitiful veil, helping to carry out an operation of collective denial and removal that strongly contributed to ensuring that racism in Italy would be solely attributed to the dictatorship. The end result being that in our country today racism is still an unresolved problem.

Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter Black lives matter

The strenuous defense of the colonialist volunteer Montanelli by many journalists and public figures of today, with the Fondazione Montanelli Bassi and other major Italian newspapers in the front line, is proof of this. From the post-war period to today, our schools and our press have stressed that in Ethiopia we have built many modern structures and roads, downplaying the fact that buildings were used for colonial administration or military barracks and roads for military expeditions. Thus racism, rape, enslavement and pedophilia, sistematically conducted in the Italian colonies by our soldiers, have been and are still today almost generally dowplayed. Case in point being the general portrayal of Montanelli’s deeds as an unusual but somehow legitimate marriage with a girl within local customs. In short, instead of stating facts as they really happened – the fact that our young and old colonial soldiers have enslaved, kept to the yoke and abused many black girls – we keep repeating that they were legitimate weddings in accordance to some local customs.

Yesterday and today, in our society freed from fascism, how did and do we deal with our colonial history and how have we made amends? It seems that Montanelli, judging from the videos of his interviews, did not make amends of sorts … but doubts may remain, being him no longer here to discuss this issue. There is no doubt, however, regarding the position of most Italian press where the travesty of that ancient marriage is constantly repeated. That so called marriege was one of many in Africa, contracted against the will of girls who yesterday were called Negros and nowadays non-EU immigrants. This marriage huphemisms would surely be a laughing matter, were it not impossible to avoid thinking about of that poor child, one of many, beaten up because she did not know how to sanctify – by using a catholic church expression meaning consuming – such a union. A travesty, in fact, condoned today by many family men, engaged in Italian politics and journalism(12).

Montanelli’s final words in summarizing his adventures to a scandalized eighteen-year-old reader who was puzzled about him justifying his African Marriage are contextually interesting. (Corriere della Sera, February 12, 2000 and reproduced online by the Montanelli Bassi Foundation on an article titled: An unjust and instrumental accusation) «I hope I have not scandalized you. If I did, it’s your fault». Indeed, this is what he said! He reversed the roles and put the blame on a girl, another who happened to stumble upon the famous journalist to whom a statue has been dedicated in everlasting memory.

If we are scandalized by seeing yongsters smearing statues, preferring instead to leave them spotless while removing from our collective conscience the racism and slavery of which Italy has stained itself for too long in the past…. well, in this case our famous journalist is right. It is not so much Montanelli at fault, but rather all of us, the directors and screenwriters of another Wedding Italian Style plot, part of the endlessly serialized Italian-style comedy. A genre, as per traditional script, which has always three main characters: Him, Her and the Bad one. In this particular case, Him being played by a disingeneous Italian volunteer in Africa, Her by an unfortunate Ethiopian child, and Bad one, who keeps well away at safe distance in today’s America of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Africa today. Whilst struggling for free in poisoned mercury wells to sift through for gold, whole families have no choice and take their children to the pits in Ghana. Photo: Lisa Kristine

![]()

Notes:

- On this form of colonial concubinage in Italian colonies in North Africa there is little research available. Italian Colonial sources (Ferdinando Martini, Alberto Pollera, etc.) reveal that from the beginning of Italian colonialism a form of coherced concubinage between Italian men and African women was quite common. It was usually called Madamato, a sexual relation that was neither marriage nor prostitution. African prostitutes were usually called by Italians sciarmutte – a distortion of an Arab expression – while concubines were called madame – a derogative use of the French world Madame. The relationships between Italians and Africans were mostly marked by colonialist patterns of domination and possession. Marriages in front of an Italian authority were extremely rare, while some marriages in local customs took place, even though Italian men seldom respect the commitments those marriages implied. Colonial soldiers and administrators, with rare exceptions, abandoned their children and their mothers in Africa at their return home.

- The Italo–Ethiopian war was particularly violent, but atrocities were committed also elsewhere by the Italian army (in Libya in particular). During World War II, Ethiopia became a base and a theatre of military operations until Italian forces were defeated in 1941, leading to the collapse of Italy’s Colonial empire in 1943. The peace treaty between Ethiopia and Italy was finalized in 1947. Agreements about Ethiopian rights to restitutions and reparations were not always respected by Italian governments.

- Indigenous round shaped hut, clad in clay and straw.

- The Faccetta Nera (little black face) song had ambiguous lyrics which referred to young African females hoping and impatiently waiting to be ‘liberated’ by their Italian saviors. Its most famous line, well known even today, is: ‘Little black face, wait and hope that your hour is about to come’.

- Before and during the colonial wars, the Fascist regime presented Africa to young Italians as a sexually attractive place also in literature and films. Colonial fictional literature, called by Giovanna Trento “erotic-love novels”, was set up around the image of a “white” colonial hero living with a submissive “black” woman, such as the novel Libia piccolo amore beduino, written by Mario Dei Gaslini in 1926. In Somalia the practice of madamato is mentioned in Ricordi somali by Perricone Violà. Movies also contained sexual allusions, such as Mario Camerini’s Il grande appello, filmed in the Horn of Africa in 1936. The beginning of the movie showing an Italian sailor boarding his ship for Africa carrying in his hand a booklet by F.T. Marinetti, the father of Futurism, titled Come si seducono le donne (How to seduce women).

- After World War II Italian military commanders who had committed crimes were not brought to trial, not only because Italian postwar governments were trying putting obstacles, but also because Washington and London were pursuing anticommunist strategies. To the point that some former colonial fascist criminals – such as Badoglio – benefited from their acknowledged extremely anticommunist positions and remained unpunished.

- Indro Montanelli, XX Battaglione eritreo. Milano: Panorama, 1936.

- Vittorio Mussolini, Voli sulle Ambe. Firenze: Sansoni Ed., 1937.

- An authoritative study on the Madamato and on racial policies in Italian colonies is Africa is: Giovanna Trento, Madamato and Colonial Concubinage in Ethiopia: A Comparative Perspective. Aethiopica 14 (2011), 184-205. Available on line. On colonial concubinage in Ethiopia there is no other extensive research available, either in Italian or in other languages.

- Fascist Italy emanated an important set of “Race Laws”in 1938, as a gesture of fraternal bondage between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Racism and segregation were addressed against various groups: Jews, Africans, colonial subjects, homosexuals, and other minorities. Starting earlier, beginning in 1935, racist legislative measures had already been emanated in the African colonies. However, while in Italy racist measures were taken rather seriously, in the colonies they only resulted in the banning of marriage ceremonies, while Madamato’s sexual relations continued, in though in a least open fashion.

- Both the colonialism of pre-Fascist and Fascist eras shared some basic characteristics, such as the search for a national identity to be fully manifesting itself, paradoxically, outside the national borders in the acquisition of colonies. Another important aspect was the centrality of the relationship ‘white man-black woman’ as part of the Italy’s undeniable ‘civilizing mission’.

- The lack of an open public assessment of racist and colonialist crimes has made it difficult for Italians to properly assess their Colonial past, especially during Fascism, to the point that in 20th century Italy colonialism remained a sort of “taboo”, until the pioneering research of Angelo Del Boca (Gli italiani in Africa orientale. La conquista dell’Impero, Roma–Bari: Laterza, 1979). However, to date, many of its aspects remain still largely unexplored. Thus, the issue of how “Italian widespread colonial culture” dealt with the representation of racism before and during Fascist times remains presently largely unresolved.

Related articles

Meeting Kurtz

Migrants; let’s help them at home

Dialogue on Africa

The irrationality of racism

The Bellomo conundrum

2 lettori hanno messo "mi piace"