Pavia, soup and battle

Since the end of the fifteenth century until 1559, Italy, particularly the Po Valley, was the theatre of eight wars between Spain and France, the two most powerful nations vying at that time for the domination of Europe. Ruled by two royal dynasties, the Valois at the end of its power and the Habsburg, which in later centuries will dominate the continent.

Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle

William Dermoyen, Pavia's battle, arras, about 1531

(Museum of Capodimonte)

In this endless confrontation stood two giants of politics and war, Francis I of France and Charles V, king of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor. It was inevitable that, above all, the struggle between the two great nations would take place in Italy, a land that at the time unparalleled for fertility, productivity, wealth, history and beauty.

Carl V of Habsburg, Emperor of Spain

Among the eight Italian wars, particularly important was the fourth, culminated in the Battle of Pavia of 1525, which decisively shifted the balance of Europe in favor of Spain. The conduct of war seemed to favour the French who, led in battle by Francis I himself, had conquered Milan in October 1524. Here however Francis I made a costly mistake. Instead of signing an advantageous peace treaty, he decided to deal a final blow to the Spanish, who had withdrawn holing up their troops in Pavia, laying siege to the ancient capital of the Lombard region.

The Spaniards resisted for three months, and when Francis I on February 24 1525 decided to attack Pavia, it was already too late since the imperial reinforcements, German and Swiss mercenaries, had in the meantime come to rescue Charles V. The French, despite having a superb cavalry, headed by Francis I who led the attack as a medieval warlord, were outnumbered and targeted from the city walls by deadly Spanish gunfire. The result was a massacre, with the French being virtually exterminated, leaving on the field more than 10,000 casualties (some sources report as many as 20,000), against a Spanish loss of less than a thousand. The carnage was so huge that it soon became legendary, with the Battle of Pavia being the source of many anecdotes and slang expressions that still give her immortal memory.

Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle

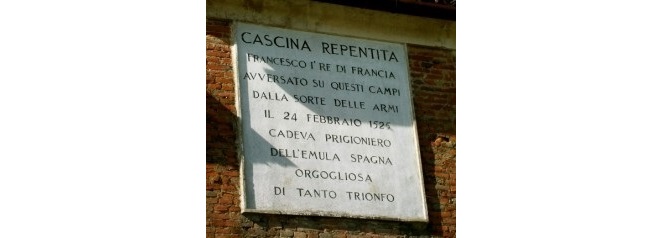

The Repentita farmhouse

Francis I was taken prisoner and brought in chains to the Repentita farmhouse, which still stands today, just north of Pavia. To a guest so illustrious as well as unexpected, it is reported that the housewife had nothing better to offer – certainly because impoverished by repeated passages of soldiers of the most diverse nationalities – than this frugal and bizarre soup .

Ingredients for 4 people

Bread, 8 slices

Butter, 120 grams (4 ounces)

8 eggs

Parmesan Cheese, 60 grams (2 ounces)

Beef broth, 1 litre (2 pints)

Salt, as needed

Fry in butter the bread slices, making sure that they remain soft inside. Take the bowls where you plan to serve the soup and lay on the bottom of each two slices of bread. For each bowl break an egg and place it on the bread slices, making sure not to break the yolk, which must remain intact. Put carefully the hot broth into each bowl making sure to pour it away from the yolks. Cover with grated Parmesan cheese. The soup is now ready to be served.

Pavia, soup and battle Pavia, soup and battle

It seems that the French king was so pleased by this strange dish, that once back in Paris, he decided to add the “Soupe à la Pavoise” in his court menu. Incidentally, and for your peace of mind in case you chance to pass by Pavia, Zuppa Pavese, the Pavia sup, is not a local dish.

All is lost, except my honor

On the evening of 24 February 1525, while a prisoner at the Repentita farm, a very bitter Francis I wrote to his mother, Louise of Savoy, a letter which contained a phrase that would become famous: tout est perdu fors l’honneur et la vie sauve qui est (all is lost, except my honor and my life which has been spared).

Francis I of France

It was undoubtedly a mistaken concept of honor, or one that was too antiquated, that pushed Francis I, sword drawn, to command the disastrous charge of his cavalry against the Spanish harquebuses. As we have learned, in accordance with the exchange rates of those times, the face value of a king’s honour was equivalent to at least 10,000 of his soldier’s lives.

Self-evident truths (Lapalissian truths)

One of those who died under the walls of Pavia was the French Marshal Jacques de la Palice (or Lapalisse). His soldiers, to honour him, composed a song that said:

« Hélas, La Palice est mort,

il est mort devant Pavie ;

hélas, s’il n’estoit pas mort

il ferait encore envie.»

(Alas, La Palice has died,

He died before Pavia;

alas, had he not died

He would still be envied.)

For assonance, the last phrase “il ferait encore envie” (he would still be envied) was commonly misinterpreted as “il serait encore en vie” (would still be alive) giving a comic effect to the funeral song. In the following century a certain Bernard de la Monnoye, who consigned the jokes on the poor Monsieur de la Palice to eternal memory, enlarged the song (with the iteration of ridiculously obvious situations and phrases). Since then in Italy “lapalissiano” is synonymous of self-evident, indicating a statement so obvious and predictable as to be ridiculous, while it is instead generally unknown that the word derives from the name of a brave soldier killed five centuries ago on the outskirts of a Lombard city.

Jean Duseigneur, bust of Jacques de La Palice (Musee de Versailles)

“Lapalissian”, Pavia soup and “All is lost, except the honor” have remained the legacy of the battle of Pavia, having endured much longer then the carcasses of horses and riders that made the city’s countryside even more fertile. Historic events and war scenarios would soon move to a theater that had become richer than Italy (the Netherlands), while the Spanish “siglo de oro” (century of gold) would soon leave camp at the appearance of a new world power: England. Everything changes quickly and everything gets lost. Except the honor, perhaps.

Arras based on drawing of Bernard von Orley, Pavia's battle,

Bruxelles 1526-1531

![]()

Italian version: Pavia, zuppa e battaglia

4 lettori hanno messo "mi piace"