Crossroads: the devil’s music

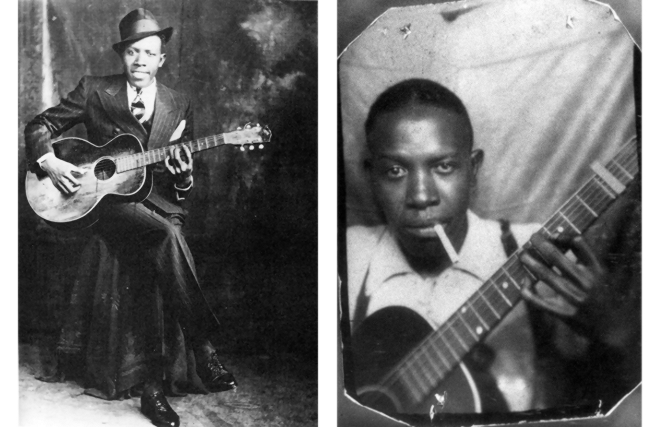

It’s nighttime. Robert has just finished playing in the most crowded place in Hazlehurts. In one hand his Gibson L1, the bottle of whiskey now almost empty in the other. He ambles around , on the moonlit road towards the cemetery, in search of a breath of air in the sweltering Mississippi summer. Arriving at a crossroads he sees, sitting, silent, and completely dressed in black, a man who seems to be waiting for him.

After that meeting he will no longer play in the same way.

I have the blue devils, I’m in an emotionally complex state. A mix of melancholy, but not sadness, a desire for life but not elation, a kind of pleasant disorientation of the senses …

The only(certain)photos of Robert Johnson

Many years have passed since that night when, it is said, Robert Johnson sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for extraordinary ability to play the blues. Perhaps by virtue of that, even today, the blues and its favorite son, rock, in certain circles, are associated with the devil, with sacrilegious transgression, with negative values, with nihilistic and self-destructive perversion, guilty of incitement and provocation against the core values of our civilization. In summary: a hymn to immorality.

[slideshow_deploy id=’16779′]

Selection from the manga by Akira Hiramoto, Me and the devil blues

Although the origins of the blues are rooted in African-American culture those reduced to slavery – for whom the rhythms and the music of the so-called gospel and spirituals were a form of liberation from their condition of misery, I believe, in a gasp of typically Christian devotion, conversely and in opposition to the expressions of all the blues and rock music in particular, are a hymn to freedom, in all its forms, to transgression, to sex. An incitement to an existence completely divorced from any conditioning of a social and religious type, in short, towards living an extreme life: pathos in all its emotional irrationalities. Melancholy, existential tension, desire, eros, rebellion.

Later on the musical production of all the sixties and seventies will be emblematic of a spirit beyond rules.

In terms of musical technique this tension is transferred harmonically in a singular fashion.

For traditional musical canons, established in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – in which the structures of the music are, mainly, organized according to a tonal rule – sentiment and its manifestations are associated with a preordained pattern.

Atmospheres of lively serenity, joy, exuberance as well as sumptuous celebration are expressed in major keys. Situations of melancholy, sadness, contemplative meditation involve the use of minor keys. This duality of expression was more pronounced in the Romantic period throughout the nineteenth century.

In the eighteenth century in fact – especially in the first half of the century – compositions are influenced by the atmospheres at court, in which the predominant aspect is that of celebration. It’s natural, therefore, that the prevailing tone of symphonies, concertos and sonatas was the major one. Think of all the production of F.J.Haydn, G.F. Handel and W.A.Mozart in comparison to that of the nineteenth-century romantic period in which the minor tonal writing assumes a more suitable character to represent the atmospheres of intimate and meditative pining: F.Chopin, above all.

F.J.Haydn, Symphony n°85 “La Reine” in B flat major

Chopin, nocturne in C-sharp minor

Of course these schematic comparisons are absolutely not be generalized (perhaps they are even trivial) and they do not attempt to construct an interpretive categorization of the complexity of a composition, but may provide a basis for a simple reading and understanding of emotive intentions of the composer.

Returning to the Devil and to the present day, in rock / blues (but also in jazz – their bit more complex and introverted cousin – in which the theme of the composition is dealt with in modal terms) musical expression has no well defined and precise tonal architectures, but moving in a modal field, it wanders around a dominant central note, in a free and unstable manner. No longer are there strict structures within which the musician must be express himself through the use of the “right notes” but the piece, freed from the canons of harmony – or rather, reading them and interpreting them in their freer and more emotional way – moves in unpredictable regions. This harmonic instability reflects the changing mind of man, in the infinite shadings and colorings of his feeling.

Robert Johnson's Gibson L1

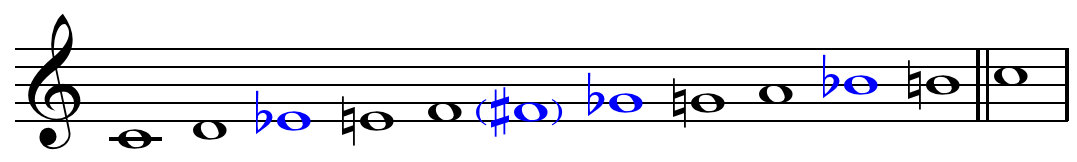

The guitar is the key instrument of the blues and rock. And on it is based on the use of scales with notes in which the modulation of the melody, disengaging itself from the classical canon, merges the major-minor tonality, overlapping, alternating and fading characteristics typical of the other tonal character of the composition. This tonal intermediation finds its fortune in what is the characteristic expression of the stringed instrument. In it, the centered pitch of the note is ensured by frets (metal frets that divide the guitar neck in precise and well defined spaces, therefore, by varying the length of the free string varies the accordingly played note). The most interesting aspect, from the technical-instrumental point of view, of the expressive ability of stringed instruments (in this case, the guitar) lies in the possibility of varying – even slightly – the centering of the note. With the use of bending – pulling, usually upward, the string of the instrument – the tone is raised by 1/4 of the base note (for other modulation effects you can also get to two tones, for other purposes) . Thus arriving at the final destination: the blue note. Without getting too technical, suffice it to say that the so-called tonality of a piece involves the use of appropriate notes that are “in place”. For example if we play the C major tonality the Eb (minor third) doesn’t “go well”, – as well as on F # and Bb “don’t work” together – you’ll need the natural E (i.e. the F and B) . But if we play blues with a tonal center C (C7, and here the question would be long …) the pentatonic scale (minor) that bluesmen employ includes “also” the use of irregular notes: notes not codified in the musical notation. An E, a G a natural B, slightly declining (obtained, aspreviously mentioned, by a slight raising of the corresponding lower tone by 1/4). Blue notes.

For example, in a blues in C you start with C7, chord that in this tonal context expresses both rest (it’s the song’s tonal center) and tension (according to the canons of Western classical harmony, harmonically the C7 “calls for” the F. It is said that it tends to resolve on the fourth degree). We are in modal atmosphere.

Such emotional uncertainty, always unstable and often on a lacerating search for a serenity that is never completely resolved, is the stylistic distinction of the blues.

You’ll find here a didactic-illustrative example of this bluesy spirit, this unstable tension between the minor and the major, in between, halfway between the two modes, between the two feelings.

If, then, the devil was involved, he was certainly well acquainted with man’s soul, and we can only celebrate the fact that, that night, he taught Robert and his disciples to transmit to us those emotions we so often find ourselves in.

And now let’s listen to the artist who is considered to be the heir of the legendary Bob: Eric “Slowhand” Clapton.

The first piece (Crossroads), written by Robert Johnson, is the emblem of the blues, and is from the concert held at Royal Albert Hall in London at the beginning of May 2005, with the late Jack Bruce on bass; the second song, the album “From The Cradle” (in fact Clapton must have inbibed blues directly from is feeding bottle …) is proposed here in the version of the wonderful concert in Hyde Park in June 1996. It synthesizes the blues singers’ pining for love and, from a technical point of view, illustrates many of the harmonics issues mentioned above.

You can run, you can run, tell my friend Willie Brown

You can run, you can run, tell my friend Willie Brown

That I got the crossroad blues this mornin’

Lord, babe, I am sinkin’ down

Have you ever loved a woman so much you tremble in pain?

For further information, some links.

On the emotional issues related to major / minor mode: here and here

On the presence of the devil in rock music and thereabouts: here

Published: April 18, 2016

We thank all of Modus’ numerous readers, who, with their continuous attention make sense of our work.

For those who would like to be informed in real-time of our online publications, and have an active profile on Facebook, we recommend giving likes on the Modus fan page: they will be able to directly link to all newly published articles.

The editorial staff

2 lettori hanno messo "mi piace"