Wakan Tanka (The Great Spirit)

Those of you, who like me, lived their childhood in the late ’50s and ’60s will remember that the most commonly used type of gift for (boys’) birthdays (birthdays and Christmas), would often refer to the conquest of the American West: rifles, guns ,wide brimmed hats and faded pants, brought us children to scenes of the westerns that we could then see in addition to the cartoons of Walt Disney.

Aside from Carnival (when a pretty feathered head surely helped creating a successful, costume though well-exploited), in everyday games, playing the part of the Indian (in the sense of First Nations) was a sad affair because it in the role playing you’d get hunted and captured while the others, the cowboys, were always the winners of those endless make-believe shootouts in which the lethal weapon was the saliva that escaped from the mouth to mimic the firing of the imaginary bullets.

Any learning about what was “good” and “bad”, of which indeed were the good and the bad guys, was reduced to the contrast between the cowboys (the good guys) and the Indians (the bad guys); all the literature and film tropes of the time reproduced this scheme with some minor variants wherein a tribe of Indians allied themselves with the palefaces to fight an opposing tribe, but always ready to betray their new white allies to reunite themselves with their kind: typical of the sterotyping trend are Captain Miki and the Great Blek, to name a few of the famous comics of the period, not to mention the western films left by John Ford and starring John Wayne.

It was a surprise for us to find out with the “revisionist” filmmaking of the late ’60s and ’70s that things had not actually gone as we had been told; I remember with great clarity the emotions I experienced in watching the movie “Soldier Blue“ where, perhaps for the first time, the story was so scandalously different than the canons that we had been served up: the natives were no longer the cruel and merciless horde that cut scalps off the whites that too close for their own good, but rather a people who wanted to live on their own land, respectful of nature and at peace with others, suffering those circumstances that had turned them into strenuous defenders of their traditions, ready to go to the ultimate sacrifice.

In Italy, as early as 1949, Sergio Bonelli was slowly attempting to introduce these “new” points of view to his comic book work; his Tex Willer character, in the Tex comics, was in no way an enemy of the Indians, he had become part of the Navajo tribe, and most of all, he was fighting the enemy tribes of his native friends.

In Italian film, Sergio Leone went on a different, more discrete, operation, launching a fortunate series of films (perhaps the most beautiful of the kind, so much so that even the Americans took to them), in which the natives basically disappeared from the scene, leaving that the good and the bad (together with the beautiful and the ugly) would share the scene, no longer in the grasslands of the plains, but often in the dusty cities of the westernmost frontier where the law was always that of the strongest; the protagonists, however, were all white (or, at best, mulatto) and natives no longer had a role.

Anyway, the dam once opened, the following films broadly revisited the whole epic, producing works that would take the point of view of those who had once been pegged as the bad guys and that, on the contrary, had been mostly taken advantage of: A Man Called Horse, Little Big Man, up to Dances with Wolves.

Rodney A. Grant and family

Wakan Tanka

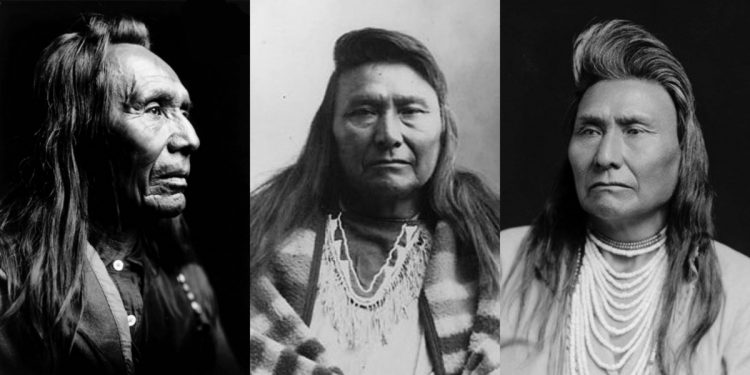

At this point that Rodney A. Grant, who I met a few years ago during one of his conferences around the world, comes into the picture and tells how the few thousand natives now live, who, having refused to completely deny their traditions, remain confined to the dusty reservations where they live together with poverty and illness, and seek, with little hope, in making their legend survive a world that no longer seems to want them.

Wind In His Hair (this was the name of the character he played alongside Kevin Kostner), is now a man, not very tall, but still imposing, severe, with a gaze that betrays the pride of his ancestors; in his life he’s had other cinematic roles but was attached to his people and came to tell us what historically really had happened.

I’m not mentioning unheard or unknown things, but I think it is worth recalling how the discovery of America was, in fact, one of the greatest tragedies that humanity has witnessed; a sort of day (instead of Columbus day) of memory dedicated to men, women and children who have been swept away by our “civilization”.

Christopher Columbus wrote of them ¹ , these Indians …”are so naive and so free with their possessions that no one who has not witnessed them would believe it.” He was in the total misunderstanding of having reached India instead of discovering a new continent but immediately caught the true essence of that people, their distinctive trait as compared to what were the Europeans: the desire to live as part of nature, in the world and not as its exploitative owners.

The roots of those indigenous civilizations, more or less are temporally parallel with our own heritage and the first finds on human presence in North America indicate that the both ancestors points of departure were near each other; yet in 1492, while those peoples showed a general lack of progress compared to their origins (still covered with animal skins and using primordial tools made of wood and stone), our European ancestors met them dressed in finely crafted robes, armed all over and already drunk with the full complement of vices that human nature could have conceived.

Conversely, those populations lived on what the land allowed, hunting for their own subsistence needs, already keenly aware that not everything is endless; we, already masters of both physics and astronomy, devoted ourselves to the intensive exploitation of the whole of the known world, while they knew that killing a female bison in the gestation season meant limiting the possibility of having more meat to eat in the future.

Their camps were made up of easy-to-install and dismantle huts, shelters and teepees, and when they left a place, this should remain as intact as possible in order to allow them to return and live there in the future with the same benefits as they had had in the past. Living in harmony with what was around them, both trees and animals, as part of a whole and not by any means the owners of everything. It is with this philosophy of life that they met us and it was also the reason for their end.

Bartolomé de Las Casas in one of his writings (Apologetic History of the Indies, p.38 ²) described that, “in this we are as barbarian to them as they to us “. Fully grasping the contradiction of a destructive modernity in the presence of a respectful archaic ethic of the world, but his words were just a drop in the sea, and where rifles and guns couldn’t, giving them diseases and plagues, of which we have always been proud exporters, did the rest. In his peregrinations, Las Casas had contacts mainly with the people of Central-South America, often far more advanced than the natives of the North, but what he said could be perfectly adapted to the latter as well.

It is estimated that in the past three hundred years, from the discovery of America to the end of the 19th century, 80-90 million people were exterminated (there can be no other way of describing their demise): men, women and children from the Andes to the enormous prairies of North America, all guilty of not having understood the importance of the wealth they possessed (gold and silver at first, lands and oil, afterwards). What remains of their pride today is scattered among the lost villages on the Andes and in few reservations in desolate corners of poverty and misery.

Notwithstanding the remarkable differences between the North American nomads compared to the Aztec, Maya and Inca in Central and South America, there has been a common destiny that has brought them together: almost total destruction. And what could not have been accomplished by the devastation of yesterday, the injustices of today, for North American natives, have survived today after enforced sterilization practices, use of chemical testing (pesticides and weapons), mineral extraction polluting aquifers, total emargination in society all of which prevent minimal levels of schooling for their children.

By now the resistance of the survivors has diminished to the bare minimum, with the increasing indifference the world seems to show towards them; nevertheless, the words ³ that one of the last great Sioux leaders, before putting down their arms and accepting the confinement to the reservation, have been utterly carved in our collective memories:

“They made us many promises, more than I can remember. But they kept but one–They promised to take our land…and they took it. “

A few years earlier, the same Red Cloud said ⁴ :

“We do not want riches but we do want to train our children right. Riches would do us no good. We could not take them with us to the other world. We do not want riches. We want peace and love. “

I close with a quote from Engels who, in his treatise “Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State“, thusly describes the social constitution of Native Americans: “… this gentile constitution, in all its childlike simplicity! No soldiers, no gendarmes or police, no nobles, kings, regents, prefects, or judges, no prisons, no lawsuits – and everything takes its orderly course. “

![]()

We thank all the many readers of Modus, that with their regular or sporadic visits give meaning to our work.

For those who would like to be informed in real-time about our publications, and have an active profile on Facebook, we recommend to add your “like” to the fan page : you will receive links to all our new articles.

The Editors

1 lettore ha messo "mi piace"